Architecting Peace: Staying Calm, Clear, and Authentic in a World of Constant Input

Walking through life towards one’s life purpose while constantly barraged by inputs

The modern world is not merely busy; it is structurally overwhelming. A substantial body of research describes information overload as a condition in which the volume, velocity, and diversity of incoming information exceed an individual’s limited cognitive processing capacity, leading to stress, impaired decision-making, and reduced well-being (Arnold, 2023; Shahrzadi et al., 2024). Research on technostress further shows that continuous digital connectivity—email, messaging platforms, notifications, and multitasking—places sustained demands on attention and working memory, particularly under conditions of existing stress (Kim et al., 2022). From a systems perspective, this means overwhelm is not a personal shortcoming or failure of discipline; it is the predictable outcome of operating a human nervous system with finite regulatory capacity inside an environment explicitly optimized to generate frequent, competing inputs.

During high-intensity periods such as the holidays, major life transitions, or sustained work pressure, this input load tends to increase rather than stabilize. Population-level surveys consistently show that a majority of adults report elevated stress during the holiday season, driven by social obligations, financial pressure, time scarcity, and emotional expectations (American Psychological Association, 2023a, 2023b, 2023c). At the same time, the digital attention environment often becomes more intrusive, with increased alerts, reminders, and media exposure. Research on alert fatigue demonstrates that repeated notifications can overwhelm attentional systems, degrade responsiveness, and ultimately lead individuals to disengage entirely by silencing or ignoring alerts (Stach et al., 2024). Many people respond to this overload by trying harder—analyzing more, pushing through discomfort, or criticizing themselves for feeling overwhelmed. However, when a system is overloaded, effort alone does not restore stability. Careful design does. Thankfully, we all have neuroplasticity so my hope is that this blog will provide some mental models and hooks that people can find useful in their life.

Systems thinking offers a more objective lens. Instead of asking, “Why can’t I handle this better?” we ask, “How does my internal system respond to sustained load, and how can it be designed to recover quickly and act intentionally?” The goal is not constant calm or emotional suppression. The goal is authentic choice—the capacity to respond in alignment with one’s deepest values and life purpose rather than reacting reflexively to fear, pressure, or urgency.

This is where the Authentic Choice State Machine intersects directly with Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy.

Frankl, a psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor, argued that the primary human drive is not pleasure or power, but meaning. Even under extreme suffering, he observed, individuals retained one irreducible freedom: the freedom to choose their attitude and response. Meaning, in Frankl’s view, is not something invented arbitrarily; it is discovered through responsibility—to one’s values, to others, and to life itself. Authentic choice, then, is not merely preference-based; it is meaning-based.

The Authentic Choice State Machine operationalizes this insight as a mental model. It translates Frankl’s philosophical and clinical observations into a practical, moment-to-moment framework for modern life. This is intended as a mental model that one can adopt, so don’t focus too much on the exact transitions between states, because these things can all happen rapidly in our minds.

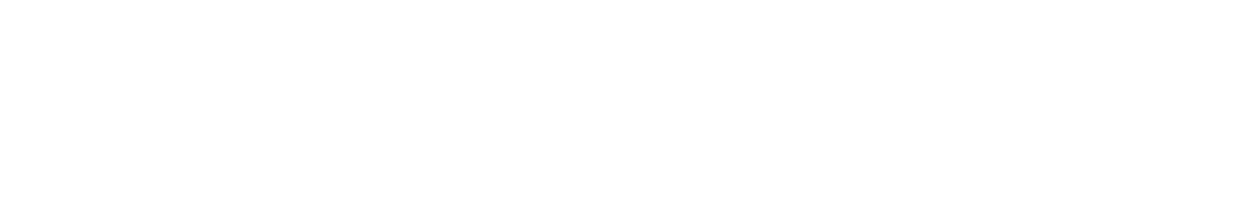

Figure 1. Authentic Choice State Machine

The system begins in READY, the regulated baseline state. READY does not mean happiness, ease, or the absence of struggle. It means the nervous system is sufficiently stable to allow choice. In Frankl’s terms, READY is the state in which a person is capable of responding to life’s demands rather than being consumed by them. Meaningful action requires this minimal internal freedom.

When an input arrives—an email, a request, a memory, a piece of news—the system does not immediately analyze or act. It first enters ORIENTING, a brief pause that establishes presence and safety. ORIENTING reflects a truth shared by neuroscience and logotherapy alike: meaning cannot be accessed when the organism perceives immediate threat. The question here is not “What should I do?” but “Am I safe enough to choose?” This pause protects against reacting from panic or conditioned fear.

From ORIENTING, the system moves into ASSESSING. This is a lightweight classification step, not deep rumination. Here the central question becomes explicitly Franklian: Does this call me toward meaning, or does it pull me into fear and compulsion? In logotherapy, meaning is revealed through values—creative values (what we contribute), experiential values (what we love or receive), and attitudinal values (the stance we take toward unavoidable suffering). ASSESSING is the moment where an input is evaluated against those dimensions.

If the input is neutral, the system returns to READY. Not every stimulus is a needs a response. If the input aligns with one’s values, mission, or sense of responsibility, the system transitions into ACTING. ACTING represents intentional engagement rooted in meaning. Importantly, authentic choice does not require comfort. Frankl was explicit that meaningful action often occurs in spite of fear, uncertainty, or pain. ACTING is therefore not about emotional ease; it is about commitment to purpose.

When an input is driven by pressure, obligation without meaning, or fear of disapproval, the system enters SETTING BOUNDARIES. From a logotherapeutic perspective, boundaries protect meaning. They prevent the dilution of one’s finite energy on demands that do not serve one’s life mission. Setting boundaries may involve refusal, delay, or re-scaling an obligation—but it may also reveal a smaller, truer action that still honors responsibility without self-betrayal.

Crucially, SETTING BOUNDARIES is not withdrawal from life. Frankl warned against nihilism and disengagement just as strongly as he warned against blind conformity. Boundaries exist to preserve one’s capacity to respond meaningfully, not to avoid responsibility.

From SETTING BOUNDARIES, the system may transition directly into ACTING if a healthy, values-aligned response becomes clear. If physiological activation remains high, the system moves into CALMING, where the priority shifts entirely to regulation. Frankl emphasized that meaning does not require constant productivity; sometimes the most responsible act is restoration. CALMING restores the internal conditions necessary for choice.

Under sustained or overwhelming load, the system may move into STRESSING, a threat-dominant state marked by hypervigilance, rumination, or collapse. In this state, meaning can feel inaccessible, and self-criticism often increases. The model is explicit: STRESSING is not a moral failure. It is a biological state. The correct response is not analysis or existential questioning, but a transition to CALMING. Only after regulation can the question of meaning be re-entered safely.

Below is a summary of each of the states and some simple mental models or hooks we can all use when we identify what state we are in.

Figure 2. Infographic with descriptions of each state along with mental models and hooks for how to think about each of them. Ignore the arrows.

Over time, repeated cycles through this system cultivate what Frankl called inner freedom—the learned confidence that one can return to meaning even after disruption. Peace, in this sense, is not the absence of suffering, but the presence of orientation. Calm becomes less about emotional perfection and more about reliable reconnection to purpose.

This framework is strongly supported by modern mental-health research. Stress physiology shows that sustained threat impairs executive function and moral reasoning, making meaning-based choice inaccessible until regulation is restored (McEwen & McEwen, 2017). Emotion-regulation research demonstrates that awareness, labeling, and values-based action are more effective than suppression (Gross, 2015). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy operationalizes values-aligned action under discomfort in ways that closely parallel logotherapy’s emphasis on meaning and responsibility (Hayes et al., 2016). Trauma-informed neuroscience underscores the necessity of safety and regulation before cognitive or existential work (Porges, 2011; van der Kolk, 2014).

Frankl’s contribution adds something essential: a moral and existential dimension. Authentic choice is not simply about self-care or stress reduction. It is about living in accordance with one’s life task—the unique responsibilities, relationships, and contributions that give one’s life coherence. Meaning may arise from faith, culture, service, creativity, love, or commitment to others. The Authentic Choice State Machine does not prescribe these values; it protects the conditions under which they can be lived.

Bill George’s work on authentic leadership offers a useful companion mental model to logotherapy: a “True North” or “north star” that anchors decisions when external pressures spike. In Authentic Leadership, George argues that durable leadership—and durable personal integrity—comes from clarity on purpose and values rather than reactive performance under pressure (George, 2003). He later expands this framing in True North: Discover Your Authentic Leadership, emphasizing an inner compass that helps people remain consistent with who they are across changing contexts and “crucible” moments (George & Sims, 2007). A complementary perspective appears in Rick Warren’s The Purpose Driven Life, which invites readers to clarify purpose as a guiding framework for daily choices, especially when life feels noisy or disorienting (Warren, 2002). Together, these perspectives reinforce the central claim of the Authentic Choice State Machine: authentic choice becomes easier when a person has explicitly named their mission and values, because those commitments function as a stable reference signal—your north star—against which modern inputs can be assessed and filtered (George, 2003; George & Sims, 2007; Warren, 2002).

In a world that increasingly profits from urgency, outrage, and distraction, peace does not happen by accident. It is engineered through repeated, humble returns to meaning. By treating the inner life as a system—one with states, transitions, and recovery paths—we move from being passive recipients of pressure to active participants in our own lives.

Authentic choice, as Frankl understood, is not freedom from difficulty, but freedom within it. And that freedom, practiced consistently, is the foundation of a meaningful life.

References (APA)

American Psychological Association. (2023a). Stress management. https://www.apa.org/topics/stress

American Psychological Association. (2023b). 2023 Holiday Stress Survey data topline. American Psychological Association.

American Psychological Association. (2023c). Even a joyous holiday season can cause stress for most Americans. American Psychological Association.

Arnold, M. (2023). Information overload: Causes, consequences, and implications for decision-making. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1182349.

Frankl, V. E. (1959/2006). Man’s search for meaning. Beacon Press.

Frankl, V. E. (1967). Psychotherapy and existentialism. Washington Square Press.

George, W. W. (2003). Authentic leadership: Rediscovering the secrets to creating lasting value. Jossey-Bass.

George, B., & Sims, P. (2007). True North: Discover your authentic leadership. Jossey-Bass.

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2014.940781

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Kim, S. Y., Lee, J. S., & Yun, S. (2022). Technostress and cognitive overload: Effects on work performance and well-being. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1523.

McEwen, B. S., & McEwen, C. A. (2017). Physiological stress responses and their impact on health and disease. Neurobiology of Stress, 7, 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2017.01.002

National Alliance on Mental Illness. (2023). Coping with stress. https://www.nami.org

Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. W. W. Norton & Company.

Shahrzadi, L., Hosseini, M., & Alizadeh, S. (2024). Causes, consequences, and coping strategies of information overload: A systematic review. Information Processing & Management, 61(1), 103399.

Stach, M., Skov, M. B., & Petersen, M. G. (2024). Investigating interaction delays and alert fatigue in smartphone notification systems. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 8(CSCW1), Article 64.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. Viking.

Warren, R. (2002). The purpose driven life: What on earth am I here for? Zondervan.

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline. (2023). https://988lifeline.org